When Nanfu Wang’s uncle became the father of a newborn baby girl in China, he didn’t celebrate. Instead, he wrapped her up in a blanket and left her on a table in a local market, in the hopes that someone would take her and raise her as their own.

Sadly, no one did. When he returned to check on her a day or so later, she was dead, her tiny face covered in bugs.

How could any parent do that you may wonder. Yet, millions of Chinese parents did over the course of 35 years while the rigid one child law was in place in China. Parents abandoned babies–mostly girls, and Chinese women aborted fetuses voluntarily or were subjected to forced abortions against their wills.

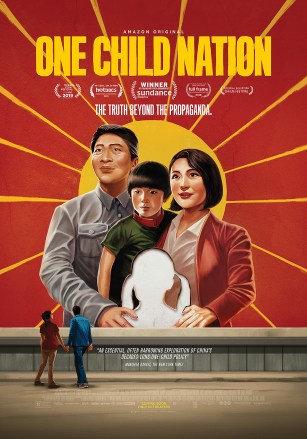

This rigid and controversial birth control policy is now the subject of a riveting new documentary you can see on Amazon Prime, One Child Nation, by filmmaker Nanfu Wang, who now lives in the U.S.

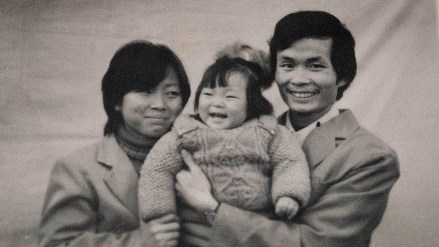

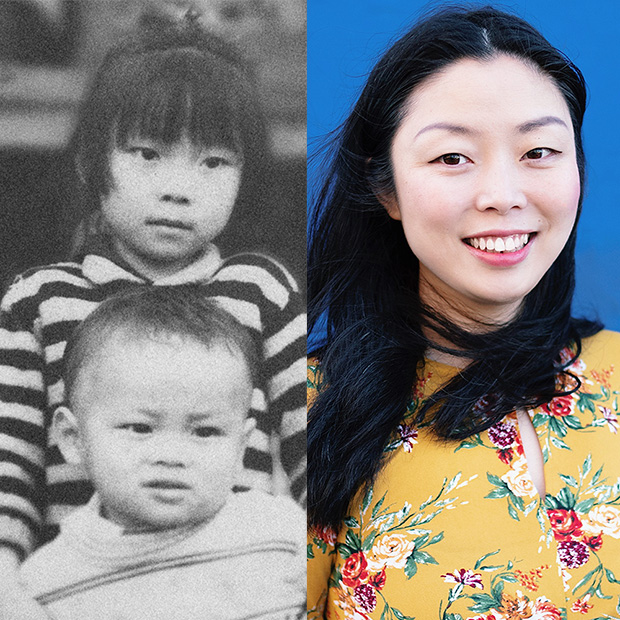

Wang grew up in a small, rural village in China as the first born child of a young couple, who welcomed her despite the fact that she was a “less desirable girl.” In China, there is a strong historical preference for male children, who parents believe will be better able to care for them in their old age. Fortunately for Wang, in rural areas, couples were sometimes allowed to have a second child, and her mother gave birth to Nanfu’s brother a few years later. But Wang’s mother has confided to her that if her second child had been born a girl, she would have abandoned or killed her.

“It made me feel like, ‘Wow, I’m happy,’ because I was the first one, because what if I was the second one? Then I wouldn’t have existed,” Nanfu told HollywoodLife in an exclusive interview.

Wang reveals that she only really thought about China’s one child policy in a critical way after she had left China to study in the U.S. and then she married here and became pregnant. “The one child policy was a thing that was background in our life…it was something that we didn’t even think about or question,” she explains.

China had introduced the draconian policy in 1979, fearing a population explosion in the country. The policy was strictly enforced by commissions created by the national and local governments. Women were monitored closely for compliance–required to take contraceptives or to be fitted with IUDs (intrauterine devices). Women who became pregnant were often forced by government officials to have abortions, even late into pregnancies. Babies that were born alive through these abortions were killed. Then many women had to undergo forced sterilizations after they had given birth to their first or second child. Nanfu’s mother was sterilized.

Four hundred million births were prevented because of this policy, the Chinese government has estimated. But the policy had other unintended consequences–the abandonment of millions of babies, many of whom perished, along with the prevalence of sex-selected abortions. Today, China has between 32 and 36 million more males than would be expected naturally. Nevertheless, it was only when Nanfu became pregnant with her son, now 2, that she seriously began to question the wisdom of the policy.

“The week after I discovered that I was pregnant, I became very protective. I wanted to do anything that I could to protect the life that I was going to bring into the world,” she relates. “I wanted to protect him not just after he was born, but for his entire life and in his future, to ensure his safety, security and happiness.”

It was then that Wang began to talk to her mother about what it was like when she had been pregnant and that she began to want to know more about what happened during the one child policy and “how that affected people.”

She decided to do her film about the one child policy in order to document it. “History tends to be written by the authority and there’s a very dominating positive version of history written by the Chinese government. In 50 or 100 years, the one child policy will no longer exist, the evidence will be gone and this history will be forever gone,” she explains. She wants future generations to find out the “alternative version of the facts that won’t be presented by the Chinese government.”

For that reason, Wang went back to her hometown as a filmmaker to talk to her family and other locals about their personal experiences with the one child policy.

Her uncle made his painful confession on camera about leaving his baby daughter to die, explaining that his mother (Nanfu’s grandmother) had threatened to commit suicide if he didn’t get rid of the baby girl so that he could have another child. “I don’t think my uncle didn’t feel guilt to abandon his child. I think you can see the pain and guilt on his face, even though he didn’t say it verbally,” she says.

Wang also interviewed a nurse who was designated as an abortionist by the government during the one child policy. She admits to performing between 50,000 and 60,000 abortions, many so late term that she had to kill the living babies once they were born. Today, she confesses that she is so guilty about what she did that she spends her time helping infertile couples conceive in hopes that with each new birth she can atone for her “sins.”

One Child Nation reveals that the one child policy was so draconian that the government would even take away one of a pair of twins from a family, and put that child up for adoption. She talks to a family that is still devastated by the forced removal of one of their toddler twin daughters, years before. She interviews members of an American organization which collects DNA from both Chinese families forced to give up or abandon children, and the Chinese children, mostly girls, who have been adopted in North America, in hopes of matching those children to their birth families. Amazingly, the organization matched the still-in-China and now teenage daughter with her now American adopted twin. The separated and long lost sisters connected on Facebook amazingly, the adoptive family went to China. “They met each other, and it was a very emotional reunion,” reveals Nanfu.

Wang and One Child Nation, are not judgemental about her uncle or her aunt–who also abandoned a baby- or even people the abortionists. “I think they all felt pain and traumatized and to a certain extent guilt…They are people like you and I. None of them are born evil or is inherently a horrible person. They did it because of the indoctrination, because they were made to believe (by the Chinese government) that it was the best thing to do and that it was the ultimately selfless thing to do for the country,” she says. “They were taught to value the country’s interests over their own individual interests. Eventually their sense of morality and what is right and wrong would be distorted.” Nanfu carefully documents, the Chinese propaganda, which was ubiquitous for three decades, promoting the necessity and goodness of the one child policy. She shows clips of the television shows, ads and local village productions promoting the benefits of a one child nation.

So effective was the government in convincing its citizens of the necessity of having just one child, that even though China rescinded the policy in 2015, few Chinese couples are now choosing to have two children. And many, including Nanfu’s mother, still believe that the policy was imperative so that there would be enough food to feed all of China’s citizens at the time.

Why does Wang believe that Chinese citizens are now voluntarily sticking to the one child policy? “Because the policy happened for over 35 years. The people who are having children now…spent their whole lives living under this one child policy and being told that having one child was the best thing. That message was everywhere,” she points out. “Then one day, the government said, “No actually two is the best. I think that’s really difficult to convince people that actually two is best, after over 30 years.”

But as for Nanfu, what does she want for herself and her family–does she want to have more than one child now?

“Yes, I do. I want my son to have a sibling.”

You can watch ‘One Child Nation’ on Amazon Prime.

Click to Subscribe to Get Our Free HollywoodLife Daily Newsletter to get the hottest celeb news.